This post is by Equal Justice Works Fellow Seth Cohen, an attorney at New York Lawyers for the Public Interest (NYLPI). Seth’s EJW Fellowship is sponsored by Johnson & Johnson and Patterson Belknap Webb & Tyler LLP.

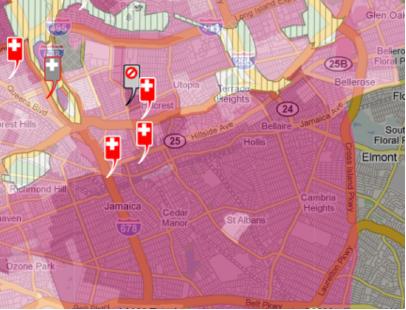

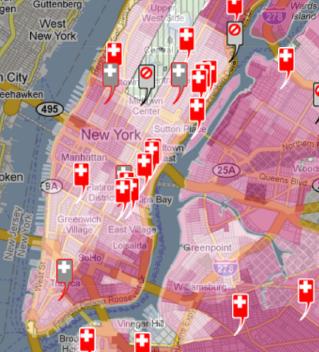

As we have written about in previous posts, Southeast Queens is a low-income community of color that has long experienced some of the worst health outcomes in New York City across a variety of measures. Despite this, and despite the fact that this community—long designated a Medically Underserved Area—has experienced a continuing trend of healthcare disinvestment. Consider this: over the past year, three hospitals that served Southeast Queens have closed; there are only 48 full-time primary care doctors per 100,000 people in Southeast Queens, almost 2/3 less than in whiter neighborhoods in Queens. All the while, Southeast Queens has the unenviable distinction of having abysmal health outcomes, including some of highest rates of infant mortality, low birth weight, and diabetes in the City.

One might think that the New York State Department of Health (DOH), the state government entity that handles all things health, would move quickly to shore up health services in a community with such a critical shortage of services and such a critical need for them. To its credit, DOH awarded $30 million in HEAL NY grants to spur healthcare services development borough-wide. Southeast Queens United in Support of Healthcare (SQUISH), a community-led coalition, advocated for allocating part of those funds toward fundamental healthcare services that Southeast Queens needs most: primary care; emergency care; and inpatient beds. The DOH grant disbursements signaled a first step—over $5 million was awarded to two community health centers that serve Southeast Queens.

Nevertheless, the grants did little to directly address the community’s most critical needs. For an area that has seen a disproportionate share of hospital and clinic closures in the borough, Southeast Queens simply did not receive funding proportionate to the critical need and unacceptable health outcomes the community faces. Indeed, it ultimately received the least amount of HEAL funding as compared to other areas in Queens.

Part of the difficulty for Southeast Queens—or any low-income community of color in New York, for that matter—is the fact that New York lacks any meaningful, structured way for people who live in the community and who use healthcare services there to provide ground-level input to DOH as to what they see as the most pressing health concerns, and how to best address those concerns. As it currently stands, DOH seems to turn a blind eye to the very individuals who actually utilize healthcare services. This perspective, though, is questionable at best, and will certainly not lead to a reduction of health inequities any time soon.

According to the National Partnership for Action to End Health Disparities, an initiative launched by the United States Department of Health and Human Services, such ground-level input is essential to eradicate health disparities. Three of the primary actions the Partnership calls for include:

- Create opportunities to engage stakeholders from all sectors in discussions and actions to ensure community responsiveness and accountability toward ending existing health disparities;

- Create mechanisms for individuals (e.g., residents, advocates) who have been affected by, or concerned with, health disparities to share their stories with the public and decision makers at all levels

- Develop or support efforts to educate legislators and elected officials about health disparities and the determinants of health

Notwithstanding these recommendations, DOH has continued to take a hands-off stance, maintaining that it is merely a “neutral” government entity unable to actively engage in or commit to correcting the systemic health inequities that persist in the community. As dispassionate and impervious as this may sound, DOH has indicated, however, that it was up to community residents to work with elected officials and other stakeholders to locate and negotiate with healthcare providers who would be willing to serve the community. Only then might DOH get involved.

So, this is exactly what SQUISH has started to do.

SQUISH has initiated conversations with Addabbo Family Health Care to prepare for leveraging any future federal dollars from healthcare reform to bring additional Federally Qualified Health Clinics (that serve predominantly Medically Underserved Areas like Southeast Queens) to the neighborhood.

SQUISH also recently met with elected officials—including Assembly Members William Scarborough, Michelle Titus, Barbara Clark, and New York City Council Member Leroy Comrie—to begin to hammer out a plan to effectively address healthcare needs in the near-term and also to craft a long-term plan to ensure quality healthcare delivery in Southeast Queens.

There is also the matter of figuring out how to influence next steps at the site of Mary Immaculate Hospital, the now-defunct hospital in Jamaica that went bankrupt and shuttered its doors approximately one year ago. The current owners of the site have indicated they “envision[] several options for redeveloping the Mary Immaculate site, including an educational facility, nonprofit organization use, government operations or a religious facility.” No doubt you can see what redevelopment option is curiously absent from this list: reusing the site to provide health services to the community. While reopening a hospital may prove a challenging enterprise, it is not unheard of. The communities of Watts and Willowbrook, low-income communities of color in Los Angeles, California that are similarly medically underserved, were recently successful in forging a pact with various stakeholders to reopen their community hospital, the King/Drew Medical Center, using federal stimulus funds. As put by one community resident affected by the lack of local healthcare services put it,

“The fact that we are in the richest and most affluent society in the world yet don’t have health and medical infrastructures in key urban cities to take care of potentially life-threatening situations is the reason we should have hospitals in communities, particularly underserved communities with large populations of uninsured.”

Three thousand miles from Watts, this sentiment is equally applicable in Southeast Queens as SQUISH continues to advocate for healthcare for its community.